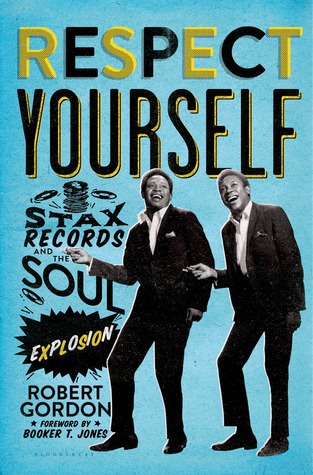

Not sure what drew me initially to Robert Gordon’s Respect Yourself: Stax Records and the Soul Explosion, but it quickly hooked me. The vibrant cover maybe. I’ve been a casual soul fan for a while and had vague notions about Otis Redding, Isaac Hayes, and Motown, but I didn’t know anything about Stax or its incredibly American zero-to-hero rise and fall in the 1960s and ’70s.

I had heard Stax songs, though, even if I didn’t know it: “Green Onions” by Booker T. and the MG’s, “Sitting on the Dock of the Bay” and “Respect” by Otis Redding (didn’t realize Aretha’s version was a cover), and “In the Midnight Hour” by Wilson Pickett among others. With this basic awareness, I don’t think I’d be able to tell the difference between the Motown and Stax sounds, but they existed:

The sign at Motown read, HITSVILLE USA. The marquee at Stax answered, SOULSVILLE USA. “That whole Memphis-soul feeling—outside of the southern nightclubs, nobody had ever heard that laid-back, barely-make-it-to-the-next-measure bluesy soul feel,” says Mar-Key Terry Johnson. “It was different from Motown with the strings and the background voices and trying to pop up black music so white people would buy it. What came out of Stax was really not a very commercial music. It’s amazing the commercial success it had.” Motown songs made you want to sing along. Stax music—you were the singer.

That surprising commercial success early on was due in large part to Stax co-founder Estelle Axton, who had set up a record shop next to the studio and basically turned it into an R&D unit:

Her store wasn’t only for moving product; it was also for developing it. “I could also test the records they made in the back. If I had one that several customers said, ‘Give me one of those too,’ I could tell them in the back, ‘Go ahead and press that one, it’ll sell.’ That’s why we were successful with nearly everything we put out for a few years—we tested them at home before we let them go.”

As Stax songs grew in popularity, so did the company. Competing with big corporations with national reach like Columbia and Atlantic meant connecting independently with distributors and radio stations all over the country and convincing them to play Stax music. That convincing often came in the illegal form of payola, which some people were brought in by Stax to do:

“I was the payola king of New York,” Weiss later bragged. “Payola was the greatest thing in the world. You didn’t have to go out to dinner with someone and kiss their ass. Just pay them, here’s the money, play the record, fuck you.” One of his Stax associates remembered Weiss as the guy who could buy a million records for a million bucks. The distribution of them might not have been clean, the sales may not all be accounted for, but the money spent, the generator whirred, and the cash register went ka-ching.

Gordon places the story of Stax firmly within the story of Memphis, a regional hotspot for blues and country music but also an ardently segregationist town and hotbed of race-related civil strife. It’s the city that spawned Sun Records and Elvis, but also a years-long labor dispute between Public Works and majority-black sanitation workers that would bring Martin Luther King Jr. to his death. Stax became an urban oasis in its early years, forging a family-like atmosphere where black and white musicians could play and record together, even if they couldn’t drink out of the same water fountain when they left.

Ecstatic studio creativity and bitter infighting. Chart-topping hits and bankruptcy. Pool parties and plane crashes. Gordon catalogs it all with verve in this aural history, using interviews with the people involved with Stax over the years, many of which are still alive. I could barely put this down, and ended up with a mile-long list of songs to check out. (An audiobook with clips of mentioned songs would have been the ideal reading experience.)

Stax, I recently learned, is still alive, surviving buyout after buyout to land as a label of Concord Music Group. The self-titled album of Nathaniel Rateliff & The Night Sweats was a recent release, and it contains a mix of spunk and soul that’s fitting for a Stax release. Here’s to many more from a legendary American institution.

Reply