When I look back on my nearly 19 years of classroom education in elementary, middle, high school, college, and grad school, I think I’ll remember my junior year AP U.S. history class in high school as my favorite. What I loved about it was what probably bored most other students in class: it was a data dump of historical facts and anecdotes; a pure, unadulterated stream of Americana. Mr. Friedberg would spend each class throughout the semester explaining persons, places, dates, key events, and political concepts from the Revolutionary War to the Clinton presidency, and I would gleefully take notes.

I had a buddy in this class who shared the same affection for the subject matter, and more importantly, the detailed note-taking thereof. We would compare notes outside of class and discuss what we were learning, so much so that after the semester we planned to create a website where we would maintain an archive of our notes in narrative form as a resource for other Web denizens, but also because we just enjoyed writing about it. I recently found one of the documents we created for this endeavor titled “Jacksonian Democracy,” which detailed the politics and people of the period between 1824 and 1848 that was defined by the attitudes, actions, and aftermath of Andrew Jackson.

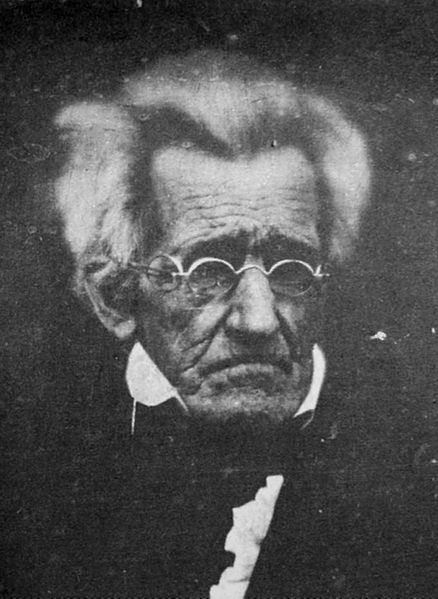

Re-reading these notes from high school was a kick because they retrod the same narrative of Andrew Jackson: His Life and Times, a biography of the seventh president by H.W. Brands that I just finished reading. In my quest to read a biography of every U.S. president (eight down, 35 to go), I recently tackled John Quincy Adams, Jackson’s presidential predecessor, bitter rival, and polar opposite. I knew after reading the JQA biography (John Quincy Adams by Paul Nagel) that I would need to read Jackson next, so I could give “Old Hickory” a fair shake after having read about him from JQA’s perspective, which, unsurprisingly, isn’t very adoring.

What I knew about the tempestuous Tennesseean before this was what most other people knew: he turned a hardscrabble upbringing into a career as a soldier, famously defeating the British at New Orleans in the War of 1812 and parlaying his fame into the first man-of-the-people election in the young nation’s history, which ushered in a new era of democratic reform. But seeing that life story rendered in detail by Brands gives me a new (qualified) appreciation for the General.

Brands’ take on the man, who was left fatherless before birth, shows a young boy deprived of formal education, adequate adult supervision, and a decent standard of living, the lack of which conspired to create a pugnacious, immature, and defiant ruffian who often (and sometimes purposefully) got in over his head. One such instance occurred during the Revolutionary War when as a 13-year-old courier he was captured by the British and implored to clean the boots of an English officer. When Jackson proudly refused the officer gashed his hand and head, leaving him with lifetime scars and a hatred of all things British. He later acquired more wounds from the countless duels he either initiated or was compelled to engage in. Seriously, I lost count of all the duels he was in one way or another involved in.

A huge part of Jackson’s life and identity was his wife Rachel. They married in the 1790s under scandalous circumstances: Rachel had divorced an abusive knave named Lewis Robards and apparently shacked up with Jackson before the divorce was finalized. Jackson’s fierce loyalty for his friends and intense hatred for anyone who betrayed that loyalty or besmirched his or his wife’s honor were revealed in this situation, in another during his presidency, and throughout his life.

Jackson’s insatiable defense of honor is what provided such a stark contrast with his predecessor Adams. Both men were children of the Revolution, though with extremely different upbringings. While Jackson was orphaned early on and as a teen fought British regulars in South Carolina, John Quincy was getting schooled at Harvard and traipsed around Europe with various Founding Fathers. JQA was self-loathing and depressed, which constantly stymied his intellectual ambitions; Jackson was a man of action, basically seeking out conflict and unabashedly fighting his way through court cases, wars, and political scandals, even while suffering through lifelong debilitating ailments. While Adams defended Jackson at times, the 1824 election imbroglio, its subsequent political skullduggery, and Adams’ Federalist leanings inevitably made him Jackson’s natural enemy.

There’s a lot not to like about Andrew Jackson. He was brash, bordering on unhinged, especially when dealing with an adversary. He could be annoyingly obstinate, like when he refused to honor or even acknowledge various Supreme Court decisions (mostly due to his ire for the federalist Chief Justice John Marshall). And, oh yeah, he owned a bunch of slaves. This, along with his involvement in the removal of Native American tribes, is usually the deal-breaker for people when considering his presidential greatness.

But his failings could also be interpreted as his strengths. His obduracy paid off for his democratic and anti-elite ideology in his fight against the banker Nicholas Biddle (yet another hated rival) and the National Bank. When faced with a tariff-induced constitutional crisisthat was spearheaded by his former VP John Calhoun and his South Carolinian brethren, Jackson brought the hammer down on his home state in favor of preserving the Union. Add to all this the fact that he narrowly escaped becoming the first assassinated president due to two pistols misfiring at point-blank range. God must have loved Andrew Jackson.

He wasn’t a lovable guy, but he was important for his time. He was the first president not from Virginia or Massachusetts, or from the elite establishment that until then had essentially dictated the course of public policy without a whole lot of input from average citizens. Jackson carried to Washington the mantle of idealized agrarianism and equality for the common man that was established by Jefferson, and from which the Jacksonian brand of democracy was sowed for future generations.

Reply